The life of Martin Luther is one of the most fascinating stories in the history of Christianity. It has all the stuff of a good novel: parental conflict, spiritual agony, life-changing moments, near-misses, princes, popes, emperors, castles, kidnapping, mobs, revolution, massacres, politics, courage, controversy, disguises, daring escapes, humor and romance. And not only is it a good story, it marks a major turning point in western history and in Christianity.

Various pictures first, with biography following:

Luther’s House in Eisenach – Age 14-17

Luther as a young monk (1522)

Pope Leo X with cardinals

Luther posts his Theses

Papal Bull excommunicating Luther

Luther burns the Papal Bull

Luther as Knight George (in disguise)

Wartburg Castle – Eisenach

Luther’s Deathbed

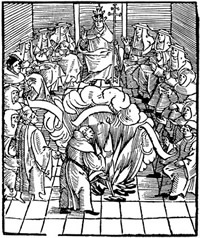

Luther at the Diet of Worms (“De-eht of Vohrms”)

Youth

Luther’s story begins in Eisleben, a small town in the region of Saxony in modern Germany. As a part of the Holy Roman Empire, 15th-century Saxony was under the political control of the Holy Roman Emperor and the religious control of the Roman pope. The Roman Catholicism into which Luther was born focused on purgatory, hell, angels, demons, sin, judgment and the saints. Jesus was depicted as an unapproachable, terrifying judge, but believers knew they could call upon the Blessed Virgin and other saints to intercede on their behalf.

On November 10, 1483, Hans and Margarethe Luther welcomed their firstborn son into the world. As was customary, the boy was named after the saint on whose feast day he was born, St. Martin.

Martin Luther was the eldest of seven children in a middle-class German peasant family. He seems to have been an unusually sensitive and religious youth. The prevalent graphic images of Christ as Righteous Judge and the agonies of hellfire terrified him.

At 21, Luther earned a Master of Arts degree from the University of Erfurt. Hans Luther was determined that his son be well-educated, and his hard work in the copper mines financed the younger Luther’s education. In May 1505, Luther entered law school in accordance with his father’s wishes. But less than a year later, his life took an unexpected turn.

That same year , while traveling back to university from his parents’ home, Luther was caught in a severe thunderstorm. Nearly hit by a bolt of lightening, he cried out in desperation to the patron saint of miners: “Help me, St. Anne, and I’ll become a monk!” Luther escaped the ordeal unharmed, and true to his word, entered a monastery within a month.

Monastic Life

Not surprisingly, the new career direction was not warmly received by the elder Luther. But the young man took the monastic life very seriously and excels at it. Still terrified of the wrath of God, he confessed sin as often as 20 times a day, punished his body by sleeping on a cold concrete floor and performed his first Mass with a trembling hand.

When he was 27, Luther was assigned to travel to the holy city of Rome to represent his monastery. The Church taught that by paying respect to relics of saints, one can earn religious merit that would shorten one’s time in Purgatory. The trip was a tremendous opportunity for the young monk, but it proved to be a profoundly disappointing experience. He was shocked by the immorality, ignorance and flippancy of the Roman priests. As he dutifully kissed each of Pilate’s stairs, he began to doubt the Church’s teachings about relics and merits. Luther returned to Saxony more troubled than ever.

Luther’s superior, Johann von Staupitz, tried to counsel the monk to stop striving and worrying and simply love God. But how could he love someone he feared so? Luther later recalled his true feelings: “Love God? I hated him!” This, of course, only added to his spiritual fear and turmoil. Finally, the exasperated Staupitz directed Luther to earn a doctorate in theology at the local University of Wittenburg, hoping the rigors of academia and helping others would force Luther to focus on things other than the state of his own soul.

A Spiritual “A-ha” Moment

Father Staupitz’ plan was far more successful than he could have imagined. Luther flourished in his new role as academic, but his thorough study of Scripture yielded an another, unexpected result – religious enlightenment. While preparing for lectures in 1513, Luther read two biblical passages that changed his life. First, he read in the Psalms the words Christ had cried out on the cross: “My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?” Luther realized with amazement that the Divine Judge had once known the very desolation he was feeling. This new perspective offered some comfort. Then, almost two years later while preparing for a lecture on the book of Romans, the professor read at verse 1:17, “The just will live by faith.”

Luther was struck by the power of the simple phrase. He meditated on its meaning for several days, and the full significance of the passage changed his life. No longer terrified of God or enslaved by the system of religious merits, Luther was finally able to rest in the knowledge that faith was all that was necessary to save him. The new perspective became evident in his lectures and conversations with other faculty, and before long his ideas became prominent at the University of Wittenburg.

One Indulgence Salesman

Meanwhile, in Rome, Pope Leo X needed funds to build St. Peter’s Basilica. Fortunately for him, the Church had as a major source of income at its disposal: the sale of indulgences. So, in 1517, Leo announced the availability of new indulgences. Those who purchase them, he announced, will not only help protect the precious relics of St. Paul and St. Peter from the ravages of rain and hail, but would receive valuable religious merit. This merit, which could be distributed at the Pope’s discretion from the treasury of merit of the saints, would alleviate the penalty of sin in this life and the next.

A Dominican monk named John Tetzel was assigned to the sale of indulgences in Saxony. A talented and unscrupulous salesman, Tetzel was willing to make any claim that improved sales. He thus promised not only a reduction in punishment for sin, but complete forgiveness of all sin and a return to the state of perfection enjoyed just after baptism.

He added that if one would generously purchase indulgences to speed the release of a deceased loved one from Purgatory, no actual repentance on the part of the giver was even necessary. Marketing genius that he was, Tetzel employed a memorable jingle to make his offer clear and simple:

“As soon as the coin in the coffer rings, a soul from Purgatory springs.”

Ninety-Five Theses

Some of those who purchased indulgences from Tetzel were Luther’s parishioners. Appalled at the abuse, Luther penned 95 statements against the practice of selling indulgences. On October 31, 1517, he nailed his 95 Theses to the door of the castle church in Wittenburg, a common method of initiating scholarly discussion.

The actual title of the famous theses is Disputation on the Power and Efficacy of Indulgences. Luther wrote them in Latin with an intended audience of his university colleagues, and could not have imagined the impact they would have on Christianity and on Europe.

But his Theses were translated into German, and using to Guttenberg’s newly-invented movable-type printing press, quickly copied and disseminated all over Saxony. The Pope himself received a copy, but he was unimpressed. He is said to have inquired, “What drunken German monk wrote these?” He directed the Augustinian order to deal with the situation.

When invited to the order’s next meeting, in April 1518, Luther feared for his life, and for good reason. Heresy had cost the lives of many reformers before him. But to his surprise, Luther found that many of his fellow friars agreed with him. Others simply regarded the issue as yet another dispute between the rivals Dominicans and Augustinians.

Diet of Augsburg

In October 1518, an imperial diet (“DEE-it”) – a meeting of the Holy Roman Empire’s princes and nobles – was held in Augsburg. The Pope sent a representative to the meeting with instructions to convince the German princes to support a crusade against the Turks. A secondary task was to meet with Luther and convince him to recant. Not entirely confident he would return home alive, Luther nevertheless attended the meeting in the hopes of defending his views.

Unfortunately, the papal representative Cardinal Cajetan showed no interest in debating issues, only in persuading Luther to recant. Like Jan Hus, who was burned at the stake for heresy 100 years prior, Luther responded that he would be glad to recant if shown his errors from the Scriptures. When he learned he was to be arrested if he refused to recant, Luther escaped by night and returned to Wittenburg.

Fortunately, politics were on his side for the moment. As one of the electors of the Holy Roman Emperor, the Pope did not wish to upset Luther’s prince, Frederick the Wise. A truce was called in which both the Pope and Luther agreed to abstain from further controversy. Of course, neither would obey the truce for long.

In July of 1519, a professor from Ingolstadt named John Eck challenged one of Luther’s colleagues at Wittenburg to an academic debate. The colleague, Karlstadt, was a convert to Luther’s way of thinking, and in fact more radical in some ways than Luther himself. (Luther later wryly remarked of his friend: “He has swallowed the Holy Spirit, feathers and all.”)

Luther accompanied Karlstadt to the debate, which was held in Leipzig. As Eck had hoped, Luther wound up participating directly. He demonstrated a superior knowledge of the Scriptures, but Eck was highly skilled in the art of debate. Luther was led to state that councils can err, and that the average Christian with the authority of Scripture has more power than a council or the Pope himself. Eck considered himself victorious, for Luther had proved himself to be a heretic just like Hus. From this point forward, anti-Lutheran propaganda often portrayed the monk as “the Saxon Hus.”

Martin Luther’s Papal Bull

Papal bull excommunicating Luther.

Excommunication

Luther spent the next year developing his ideas, teaching, and writing. His most important treatises of this period include Address to the German Nobility, On the Babylonian Captivity of the Church, and Freedom of a Christian.

On October 10, 1520, Luther received a papal bull (official proclamation from the Pope). Entitled Exsurge Domine (“Arise, O Lord”), the bull began by dramatically appealing to God to protect his church from the threat of Luther.

Arise, O Lord, and defend Thy cause!

A wild boar has invaded Thy vineyard.

Less poetic was the papal bull’s sober message that Luther would be excommunicated if he did not recant within 60 days. In Catholic doctrine, in which salvation is only available through the church, excommunication amounts to eternal damnation.

Luther, once a trembling Catholic kissing each of Pilate’s steps in Rome, publicly cast the bull into a bonfire. He was officially excommunicated by the Pope on January 3, 1521.

Diet of Worms

Emperor Charles V opened the imperial Diet of Worms (pronounced “DEE-it of Vorms”) on 22 January 1521. Luther was summoned to renounce or reaffirm his views and was given an imperial guarantee of safe-conduct to ensure his safe passage. When he appeared before the assembly on 16 April, Johann Eck, an assistant of Archbishop of Trier, acted as spokesman for the Emperor. (Bainton, p. 141) He presented Luther with a table filled with copies of his writings. Eck asked Luther if the books were his and if he still believed what these works taught. Luther requested time to think about his answer. It was granted.

Luther prayed, consulted with friends and mediators and presented himself before the Diet the next day. When the counselor put the same questions to Luther, he said: “They are all mine, but as for the second question, they are not all of one sort.” Luther went on to say that some of the works were well received by even his enemies. These he would not reject.

A second class of the books attacked the abuses, lies and desolation of the Christian world. These, Luther believed, could not safely be rejected without encouraging abuses to continue.

The third group contained attacks on individuals. He apologized for the harsh tone of these writings, but did not reject the substance of what he taught in them. If he could be shown from the Scriptures that he was in error, Luther continued, he would reject them. Otherwise, he could not do so safely without encouraging abuse.

Eck, after countering that Luther had no right to teach contrary to the Church through the ages, asked Luther to plainly answer the question: Would Luther reject his books and the errors they contain? Luther replied:

“Unless I am convicted by Scripture and plain reason — I do not accept the authority of popes and councils, for they have contradicted each other — my conscience is captive to the Word of God. I cannot and will not recant anything, for to go against conscience is neither right nor safe.”

According to tradition, Luther is then said to have spoken these famous words:

“Here I stand. I can do no other. God help me. Amen.” (Bainton, pp. 142-144)

Private conferences were held to determine Luther’s fate. Before a decision was reached, Luther left Worms. During his return to Wittenberg, he disappeared. The Emperor issued the Edict of Worms on May 25, 1521, declaring Martin Luther an outlaw and a heretic and banning his literature.

A Nighttime Kidnapping and Exile in Wartburg

Luther’s disappearance after the Diet of Worms was planned. Frederick the Wise arranged for Luther to be seized on his way from the Diet by a company of masked horsemen, who carried him to Wartburg Castle at Eisenach, where he stayed for about a year. He grew a wide flaring beard, took on the garb of a knight, and assumed the pseudonym Jörg (or “Knight George”). During this period of forced sojourn in the world, Luther was still hard at work upon his celebrated translation of the New Testament, though he couldn’t rely on the isolation of a monastery.

With Luther’s residence in the Wartburg began the constructive period of his career as a reformer; while at the same time the struggle was inaugurated against those who, claiming to proceed from the same Evangelical basis, were deemed by him to swing to the opposite extreme and to hinder, if not prevent, all constructive measures. In his “desert” or “Patmos” (as he called it in his letters) of the Wartburg, moreover, he began his translation of the Bible, of which the New Testament was printed in September 1522. Here, too, besides other pamphlets, he prepared the first portion of his German postilla and his Von der Beichte, in which he denied compulsory confession, although he admitted the wholesomeness of voluntary private confessions.

He also wrote a polemic against Archbishop Albrecht, which forced him to desist from reopening the sale of indulgences; while in his attack on Jacobus Latomus he set forth his views on the relation of grace and the law, as well as on the nature of the grace communicated by Christ. Here he distinguished the objective grace of God to the sinner, who, believing, is justified by God because of the justice of Christ, from the saving grace dwelling within sinful man; while at the same time he emphasized the insufficiency of this “beginning of justification,” as well as the persistence of sin after baptism and the sin still inherent in every good work.

Wartburg Castle

Although his stay at Wartburg kept Luther hidden from public view, Luther often received letters from his friends and allies, asking for his views and advice. For example, Philipp Melanchthon wrote to him and asked how to answer the charge that the reformers neglected pilgrimages, fasts and other traditional forms of piety. Luther’s replied: “If you are a preacher of mercy, do not preach an imaginary but the true mercy. If the mercy is true, you must therefore bear the true, not an imaginary sin. God does not save those who are only imaginary sinners. Be a sinner, and let your sins be strong, but let your trust in Christ be stronger, and rejoice in Christ who is the victor over sin, death, and the world. We will commit sins while we are here, for this life is not a place where justice resides. We, however, says Peter (2. Peter 3:13) are looking forward to a new heaven and a new earth where justice will reign.” (Letter 99.13, To Philipp Melanchthon, 1 August 1521.)

Meanwhile some of the Saxon clergy, notably Bernhardi of Feldkirchen, had renounced the vow of celibacy, while others, including Melanchthon, had assailed the validity of monastic vows. Luther in his De votis monasticis, though more cautious, concurred, on the ground that the vows were generally taken “with the intention of salvation or seeking justification.” With the approval of Luther in his De abroganda missa privata, but against the firm opposition of the prior, the Wittenberg Augustinians began changes in worship and did away with the mass. Their violence and intolerance, however, were displeasing to Luther, and early in December he spent a few days among them. Returning to the Wartburg, he wrote his Eine treue Vermahnung . . . vor Aufruhr und Empörung; but in Wittenberg Carlstadt and the ex-Augustinian Zwilling demanded the abolition of the private mass, communion in both kinds, the removal of pictures from churches, and the abrogation of the magistracy

Around Christmas, Anabaptists from Zwickau added to the anarchy. Thoroughly opposed to such radical views and fearful of their results, Luther entered Wittenberg on March 7, and the Zwickau prophets left the city. The canon of the mass, giving it its sacrificial character, was now omitted, but the cup was at first given only to those of the laity who desired it. Since confession had been abolished, communicants were now required to declare their intention, and to seek consolation, under acknowledgment of their faith and longing for grace, in Christian confession. This new form of service was set forth by Luther in his Formula missæ et communionis (1523), and in 1524 the first Wittenberg hymnal appeared with four of his own hymns. Since, however, his writings were forbidden by Duke George of Saxony, Luther declared, in his Ueber die weltliche Gewalt, wie weit man ihr Gehorsam echuldig sei, that the civil authority could enact no laws for the soul, herein denying to a Roman Catholic government what he permitted an Evangelical.

The Peasants’ War

The Peasants’ War (1524-1525) was in many ways a response to the preaching of Luther and other reformers. Revolts by the peasantry had existed on a small scale since the 14th century, but many peasants mistakenly believed that Luther’s attack on the Church and its hierarchy meant that the reformers would support an attack on the social hierarchy as well. Because of the close ties between the hereditary nobility and the princes of the Church that Luther condemned, this is not surprising. Revolts that broke out in Swabia, Franconia, and Thuringia in 1524 gained support among peasants and some disaffected nobles. Gaining momentum and a new leader in Thomas Münzer, the revolts turned into an all-out war, the experience of which played an important role in the founding of the Anabaptist movement.

Initially, Luther seemed to many to support the peasants, condemning the oppressive practices of the nobility that had incited many of the peasants. As the war continued, and especially as atrocities at the hands of the peasants increased, Luther came out forcefully against the revolt; since Luther relied on support and protection from the princes, he was afraid of alienating them. In Against the Murderous, Thieving Hordes of Peasants (1525), he encouraged the nobility to visit swift and bloody punishment upon the peasants. Many of the revolutionaries considered Luther’s words a betrayal. Others withdrew once they realized that there was neither support from the Church nor from its main opponent. The war in Germany ended in 1525, when rebel forces were put down by the armies of the Swabian League.

Luther resented Germany’s domination by a group of clergymen based in Rome, and these nationalist feelings may have motivated the Reformation to some extent. During the Peasants’ War, Luther continued to stress obedience to secular authority; many may have interpreted this doctrine as endorsement of absolute rulers, leading to acceptance of monarchs and dictators in German history.

Luther’s Death and Legacy

Luther died in Eisleben, the same town in which he was born, on 18 February, 1546.

Martin Luther’s bold rebellion, more than the other religious dissenters that preceded him, led to the Protestant Reformation. Thanks to the printing press, his pamphlets were well-read throughout Germany, and soon other thinkers developed other Protestant sects. Since Protestant countries were no longer bound to the powerful Roman Catholic Church, an expanded freedom of thought developed which probably contributed to Protestant Europe’s rapid intellectual advancement in the 17th and 18th centuries.

On the darker side, Roman Catholics waged bitter and ferocious wars of religion against Protestants. A century after Luther’s protests, a revolt in Bohemia ignited the Thirty Years’ War, which ravaged much of Germany. And Luther’s violent writings against the Jews may well have strengthened medieval and modern anti-Semitism in Europe.

Both for better and for worse, the legacy of Martin Luther’s massive personality is still felt across the western world.

Other References on Luther’s Life

* Martin Luther – Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy

Full-length article on Luther’s life and philosophical thought, with bibliography and links, by David Whitford of Claflin University.

* Bugenhagen’s sermon at Luther’s funeral

Courtesy of Emory University.

* Philip Melancthon’s account of Luther’s life, Part 1 and Part 2

Courtesy of Project Wittenberg.

* A Mighty Fortress Is Our God: Martin Luther

A German website dedicated to Luther.

* The City of Eisleben

A virtual tour of Luther’s hometown.

Books on Luther’s Life

* Here I Stand: A Life of Martin Luther

Roland H. Bainton (Abingdon-Cokesbury P, 1950). The classic biography.

* Young Man Luther: A Study in Psychoanalysis and History

Erik H. Erikson (1958, reprinted 1993). A psychological biography.

* Luther: An Experiment in Biography

H.G. Haile (Doubleday, 1980). Concentrates on the last 10 years of Luther’s life.

* Luther the Reformer: The Story of the Man and His Career

James M. Kittleson (1986). An introduction suitable for readers new to the Reformation. “This single-volume biography has become a standard resource for those who wish to delve into the depths of the Reformer without drowning in a sea of scholarly concerns.”

* Martin Luther: The Man and His Work

Walther Von Loewenich (1986; German 1982).

* Luther: Man Between God and the Devil

Heiko Oberman (Image Books, 1992; German orig. ed., 1989). “Oberman believes that we can best understand Martin Luther as a man of the Middle Ages who believed that he was literally involved in a mortal struggle with the devil incarnate and that the pope was the Antichrist of the Last Days. The original German edition of this brilliant, sympathetic psychobiography of the father of the Reformation won the Historischer Sachbuchpreis, a special prize given the outstanding historical work of the decade 1975-85.”

* The Legacy of Luther

Ernst Walter Zeeden (1954; German 1950).

Luther’s Life on Film

1. 1953: Martin Luther, theatrical film, with Niall MacGinnis as Luther; directed by Irving Pichel. Academy Award nominations for black & white cinematography and art/set direction. Rereleased in 2002 on DVD in 4 langauges.

2. 1973: Luther, theatrical film (MPAA rating: PG), with Stacy Keach as Luther.

3. 1992: Where Luther Walked, documentary directed by Ray Christensen.

4. 2001: Opening the Door to Luther, travelogue hosted by Rick Steves. Sponsored by the ELCA.

5. 2002: Martin Luther, a historical film from the Lion TV/PBS Empires series, with Timothy West as Luther, narrated by Liam Neeson and directed by Cassian Harrison.

6. 2003: Luther, theatrical release (MPAA rating: PG-13), with Joseph Fiennes as Luther and directed by Eric Till. Partially funded by American and German Lutheran groups